High-fiber Diet Keeps Gut Microbes from Eating the Colon’s lining, Protects Against Infection

Posted: December 9, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentThis DOES NOT mean a diet high in barn muffins o9r cereals. You need fiber from fruits and vegetables!

November 17, 2016

University of Michigan Health System

When microbes inside the digestive system don’t get the natural fiber that they rely on for food, they begin to munch on the natural layer of mucus that lines the gut, eroding it to the point where dangerous invading bacteria can infect the colon wall, new research in mice shows.

When mice were raised germ-free, then given a transplant of human gut microbes, the impact of fiber on their colons could be seen. Mice fed a high-fiber diet maintained a thick mucus layer along the lining of their colons, while those that received a fiber-free diet saw the mucus layer grow thinner as bacteria capable of digesting mucus proliferated. The thin layer allowed a pathogen bacteria access to the cells of the colon wall.

It sounds like the plot of a 1950s science fiction movie: normal, helpful bacteria that begin to eat their host from within, because they don’t get what they want.

But new research shows that’s exactly what happens when microbes inside the digestive system don’t get the natural fiber that they rely on for food.

Starved, they begin to munch on the natural layer of mucus that lines the gut, eroding it to the point where dangerous invading bacteria can infect the colon wall.

In a new paper in Cell, an international team of researchers show the impact of fiber deprivation on the guts of specially raised mice. The mice were born and raised with no gut microbes of their own, then received a transplant of 14 bacteria that normally grow in the human gut. Scientists know the full genetic signature of each one, making it possible to track their activity over time.

The findings have implications for understanding not only the role of fiber in a normal diet, but also the potential of using fiber to counter the effects of digestive tract disorders.

“The lesson we’re learning from studying the interaction of fiber, gut microbes and the intestinal barrier system is that if you don’t feed them, they can eat you,” says Eric Martens, Ph.D., an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Michigan Medical School who led the research along with his former postdoctoral fellow Mahesh Desai, Ph.D., now at the Luxembourg Institute of Health.

Using U-M’s special gnotobiotic, or germ-free, mouse facility, and advanced genetic techniques that allowed them to determine which bacteria were present and active under different conditions, they studied the impact of diets with different fiber content — and those with no fiber. They also infected some of the mice with a bacterial strain that does to mice what certain strains of Escherichia coli can do to humans — cause gut infections that lead to irritation, inflammation, diarrhea and more.

The result: the mucus layer stayed thick, and the infection didn’t take full hold, in mice that received a diet that was about 15 percent fiber from minimally processed grains and plants. But when the researchers substituted a diet with no fiber in it, even for a few days, some of the microbes in their guts began to munch on the mucus.

They also tried a diet that was rich in prebiotic fiber — purified forms of soluble fiber similar to what some processed foods and supplements currently contain. This diet resulted in the same erosion of the mucus layer as observed in the lack of fiber.

The researchers also saw that the mix of bacteria changed depending on what the mice were being fed, even day by day. Some species of bacteria in the transplanted microbiome were more common — meaning they had reproduced more — in low-fiber conditions, others in high-fiber conditions.

And the four bacteria strains that flourished most in low-fiber and no-fiber conditions were the only ones that make enzymes that are capable of breaking down the long molecules called glycoproteins that make up the mucus layer.

In addition to looking at the of bacteria based on genetic information, the researchers could see which fiber-digesting enzymes the bacteria were making. They detected more than 1,600 different enzymes capable of degrading carbohydrates — similar to the complexity in the normal human gut.

Just like the mix of bacteria, the mix of enzymes changed depending on what the mice were being fed, with even occasional fiber deprivation leading to more production of mucus-degrading enzymes.

Images of the mucus layer, and the “goblet” cells of the colon wall that produce the mucus constantly, showed the layer was thinner the less fiber the mice received. While mucus is constantly being produced and degraded in a normal gut, the change in bacteria activity under the lowest-fiber conditions meant that the pace of eating was faster than the pace of production — almost like an overzealous harvesting of trees outpacing the planting of new ones.

When the researchers infected the mice with Citrobacter rodentium — the E. coli-like bacteria — they observed that these dangerous bacteria flourished more in the guts of mice fed a fiber-free diet. Many of those mice began to show signs of illness and lost weight.

When the scientists looked at samples of their gut tissue, they saw not only a much thinner or even patchy mucus later — they also saw inflammation across a wide area. Mice that had received a fiber-rich diet before being infected also had some inflammation but across a much smaller area.

Martens notes that in addition to the gnotobiotic facility, the research was possible because of the microbe DNA and RNA sequencing capability built up through the Medical School’s Host Microbiome Initiative, as well as the computing capability to plow through all the sequence data.

“Having all the resources here was the key to making this work, and the fact that it was all across the street from our lab allowed us to pin it all together,” he says. He also notes the role of U-M colleagues led by Gabriel Nunez and Nobuhiko Kamada in providing the C. rodentium pathogen model, and of French collaborators from the Aix-Marseille Université in studying the enzymes in the mouse gut.

Going forward, Martens and Desai intend to look at the impact of different prebiotic fiber mixes, and of diets with more intermittent natural fiber content over a longer period. They also want to look for biomarkers that could tell them about the status of the mucus layer in human guts — such as the abundance of mucus-digesting bacteria strains, and the effect of low fiber on chronic disease such as inflammatory bowel disease.

“While this work was in mice, the take-home message from this work for humans amplifies everything that doctors and nutritionists have been telling us for decades: Eat a lot of fiber from diverse natural sources,” says Martens. “Your diet directly influences your microbiota, and from there it may influence the status of your gut’s mucus layer and tendency toward disease. But it’s an open question of whether we can cure our cultural lack of fiber with something more purified and easy to ingest than a lot of broccoli.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Michigan Health System. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Eating a Handful of Nuts Each Day Could Help You Live Longer

Posted: December 7, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a comment

From Gizmodo

A sweeping analysis of current research shows that people who eat at least 20 grams of nuts each day are less likely to develop potentially fatal conditions such as cancer and heart disease.

New research published in BMC Medicine is highlighting the impressive health benefits from the regular consumption of nuts such as pecans, hazel nuts, walnuts, and even peanuts (which are technically legumes). Eating just 20 grams of nuts each day was linked to a 30 percent reduction in coronary heart disease, a 15 percent reduction in cancer, and a 22 percent reduction in premature death. Nut consumption was also associated with a reduced risk of dying from respiratory disease and diabetes, although these correlations were weaker and involved smaller sample sizes.

Those are impressive numbers by any measure. Previous research managed to link nut consumption with a reduced risk of heart disease and “all cause mortality,” i.e. literally any cause of death, but potential associations with more unusual causes of death had not been thoroughly studied.

To address this oversight, a research team from Imperial College London and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology pooled together 29 published studies from around the world to conduct the most exhaustive analysis of current research on nut consumption and its associated health benefits to date.

Collectively, these studies involved upwards of 819,000 participants, and included more than 12,000 cases of coronary heart disease, 9,000 cases of stroke, 18,000 cases of cardiovascular disease and cancer, and more than 85,000 deaths. Differences between the populations were studied (e.g. differences between men and women, or people with different risk factors), but even accounting for these factors, researchers consistently found that nut consumption could be linked to a reduction in disease.

“It’s quite a substantial effect for such a small amount of food.”

“We found a consistent reduction in risk across many different diseases, which is a strong indication that there is a real underlying relationship between nut consumption and different health outcomes,” noted study co-author Dagfinn Aune from Imperial College London in a statement. “It’s quite a substantial effect for such a small amount of food.”

It’s important to point out that correlation is not causation; this study didn’t look into the physiological mechanisms that may account for the dramatic reduction in disease risk. It’s possible, for example, that nut consumption is tied to other types of healthy eating habits (e.g. people who consume nuts may be health-oriented types who eat lots of vegetables and fruits, too).

That said, the nutritional value of nuts is hardly a secret. Nuts contain high amounts of fiber, magnesium, and polyunsaturated fats—nutrients that play a key role in cutting cardiovascular risk and reducing cholesterol levels.

“Some nuts, particularly walnuts and pecan nuts are also high in antioxidants, which can fight oxidative stress and possibly reduce cancer risk,” added Aune. “Even though nuts are quite high in fat, they are also high in fiber and protein, and there is some evidence that suggests nuts might actually reduce your risk of obesity over time.”

Sadly, the researchers weren’t able to conclude whether peanut butter offers the same health benefits, but say it’s “possible that the added sugar or salt in peanut butter could counteract any beneficial effects of plain peanuts.” Which brings up a good point: excessive amounts of salt on your nuts may negate some of these health benefits. Also, the researchers found that eating more than 20 grams of nuts each day didn’t improve health outcomes any further, so no need to start binging on nuts.

Vitamin D Status in Newborns and Risk of MS in Later Life

Posted: December 5, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentMost Americans are deficient in Vitamin D. We have become terrified of getting skin cancer. BUT, LACK of Vitamin D leads to cancer because we need it to build an immune system. You need sun on BARE Skin everyday. It needs to be on skin that hasn’t been stripped of oils. I use no soap on my skin, only a loofah. Then DO NOT shower immediately upon coming indoors. Vitamin D is absorbed from the oil on the skin over the coarse of a few hours.

Babies born with low levels of vitamin D may be more likely to develop multiple sclerosis (MS) later in life than babies with higher levels of vitamin D, according to a study published in the November 30, 2016, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“More research is needed to confirm these results, but our results may provide important information to the ongoing debate about vitamin D for pregnant women,” said study author Nete Munk Nielsen, MD, MSc, PhD, of the State Serum Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark.

In Denmark, dried blood spots samples from newborn screening tests are stored in the Danish National Biobank. Researchers identified everyone in Denmark who was born since April 30, 1981, had onset of MS by 2012 and whose dried blood spots samples were included in the biobank. The blood from those 521 people was then compared to that of 972 people of the same sex and birthday who did not have MS. In this study, newborns with levels of vitamin D less than 30 nanomoles per liter (nmol/L) were considered born with deficient levels. Levels of 30 to less than 50 nmol/L were considered insufficient and levels higher than or equal to 50 nmol/L were considered sufficient.

The study participants were divided into five groups based on vitamin D level, with the bottom group having levels of less than 21 nmol/L and the top group with levels higher than or equal to 49 nmol/L. There were 136 people with MS and 193 people without MS in the bottom group. In the top group, there were 89 people with MS and 198 people without the disease. Those in the top group appeared to be 47 percent less likely to develop MS later in life than those in the bottom group.

Nielsen emphasizes that the study does not prove that increasing vitamin D levels reduces the risk of MS.

The study has several limitations. Dried blood spots samples were only available for vitamin D analysis for 67 percent of people with MS born during the time period. Vitamin D levels were based on one measurement. Study participants were 30 years old or younger, so the study does not include people who developed MS at an older age. In addition, the Danish population is predominantly white, so the results may not be generalizable to other populations. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that this apparent beneficial effect could be mediated through other factors in later life such as vitamin D levels, in which case a possible maternal vitamin D supplementation would not reduce the MS risk in the offspring.

Sources of vitamin D are diet, supplements and the sun. Dietary vitamin D is primarily found in fatty fish such as salmon or mackerel. Levels of vitamin D should be within the recommended levels, neither too low nor too high.

Story Source:

Materials provided by American Academy of Neurology (AAN). Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

MORE READING-

Vitamin D- The Most Important Nutrient

The Surprising Connection Between Whey Protein And Acne

Posted: December 2, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentYou probably know my stance on dairy, that it has no place in a humans body.

From Self

After a workout, many of us scoop some protein powder into a smoothie or scarf down a protein bar to get some quick fuel on-the-go. It’s convenient nutrition that tides you over until you can sit down for a legit meal. But recent research is suggesting that most people’s go-to protein, whey, isn’t as good for skin as it is for muscles. In fact, the milk-derived protein has been linked to acne breakouts.

A few studies done in the past five years have linked whey protein and acne. “The hardcore evidence is skimpy,” Hilary Baldwin, M.D., acne expert and medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in Morristown, New Jersey, tells SELF, but the findings, mixed with anecdotal evidence, present a strong case for eliminating whey if stubborn acne is an issue.

The studies done were small—like, 30 patients or fewer small—but found that many people’s skin cleared up when they cut whey protein from the diet, or conversely, acne increased when adding in whey. Even those whose acne didn’t clear up with traditional meds, including isotrentinoin (Accutane), started to see results. “They failed to respond to traditional therapy until whey protein was discontinued,” says Baldwin.

The reason whey may cause acne is unknown, but there are a few theories. Studies have suggested connection between dairy in general and acne, specifically low or nonfat dairy, which points to whey as a potential culprit. “Whey is a part of milk. It’s mostly what’s left in a skim product,” Baldwin says. After the fat is skimmed off to make cream and the curds removed to make cheese, the liquid whey is what’s left. “That’s what gets dried out and made into [protein] powder,” Baldwin explains.

“If whey does cause acne, one of the theories is that it might do it by increasing insulin and insulin-like growth factor,” Baldwin explains. Whey encourages the production of a peptide in the gut that then stimulates production of the hormone insulin. Since, in addition to its role in blood sugar regulation, insulin is known to influence sebum production, an increase can create the perfect environment for acne.

Though the studies leave us with mere associations and a need for more conclusive research, Baldwin says that she and other dermatologists she’s spoken with have seen eliminating whey work first-hand. “Everyone I speak to has said they’ve seen this in at least two or three patients,” Baldwin says. If you add up all those unpublished cases, that’s a significant amount, she adds.

Baldwin describes two teenage patients of hers who were failing to respond to isotrentinoin after a few months on the medication. “It’s kind of unheard of for isotrentinoin to not work over three months,” she notes. The powerful anti-acne medication is usually a last resort for those who have tried every other option to no avail. In each case, when she asked the patient to stop using whey protein, their skin began to clear in about one month.

Of course, everyone is different, and foods that trigger acne in one person might not in another. “There are a ton of people consuming milk and whey protein and hideous junk food diets who don’t have acne—and vice versa,” Baldwin says.

If you can’t figure out what’s causing your breakouts and you eat whey protein, cut it out of your diet and see if you notice a difference. Baldwin suggests giving it two months to be able to notice a clear difference (or not). If you find that whey is sabotaging your skin? There are plenty of other protein alternatives out there. If you like having a convenient option, opt for plant-based powders and bars from brands like Vega (which offers both powders and snack bars) and Plnt by Vitamin Shoppe—both use plant proteins like pea and hempseed instead.

MIllie- My recommendation is Spirulina powder.

Forget Counting Calories, Fat and Sugar – Taking Care of your Gut is What Matters

Posted: December 1, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentIn weight loss, calorie counting and exercise have almost no impact on weight loss. Truly nourishing yourself and making sure your are actually absorbing nutrients is crucial.

From Independent– Geneticist Professor Tim Spector wants to transform how we approach eating

Ditching restrictive dieting and calorie-counting is the key to maintaining a healthy weight according to a leading scientist determined to change how we eat.

Instead, the secret to health is nurturing the microbes in our guts, according to Professor Tim Spector, a geneticist at King’s College London.

Professor Spector told The Independent that counting sugar, fat and calories is the wrong way to approach food. “Eat as much as you want, just think of your microbes,” he says.

“We have about 100 trillion microbes inside our body in the lower intestine or colon and a microbe is anything you need a microscope to see. We generally talk about bacteria, but there are viruses and fungi too and they all contribute to our health.”

Microbes help to digest food, are crucial to the immune system, and provide about a third of the body’s vitamins and chemicals. The food a person eats affects the health of their microbiome, with emerging research suggesting it can change our body’s response to medication, too.

“We are all unique in our microbes, which explains why we respond differently to foods,” explains Professor Spector.

There are three rules that everyone can following, Professor Spector says, to promote a diverse microbiome: eat real food that is not processed, increase fiber intake, and have a diverse diet.

“You don’t have to cut anything out of your diet. I’m against excluding real food,” he stresses.

The average person can, therefore, eat dairy, small amounts of meat, and carbohydrates. The best diet is one that is varied, and doesn’t include the same foods every day.

Changes in the Diet Affect Epigenetics Via the Microbiota

Posted: November 29, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentIn other words- EAT for Fruits and Veggies- and plenty of them. No, suppleness DO NOT take the place of real, live food!

You are what you eat, the old saying goes, but why is that so? Researchers have known for some time that diet affects the balance of microbes in our bodies, but how that translates into an effect on the host has not been understood. Now, research in mice is showing that microbes communicate with their hosts by sending out metabolites that act on histones–thus influencing gene transcription not only in the colon but also in tissues in other parts of the body. The findings publish November 23 in Molecular Cell.

“This is the first of what we hope is a long, fruitful set of studies to understand the connection between the microbiome in the gut and its influence on host health,” says John Denu, a professor of biomolecular chemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and one of the study’s senior authors. “We wanted to look at whether the gut microbiota affect epigenetic programming in a variety of different tissues in the host.” These tissues were in the proximal colon, the liver, and fat tissue.

In the study, the researchers first compared germ-free mice with those that have active gut microbes and discovered that gut microbiota alter the host’s epigenome in several tissues. Next, they compared mice that were fed a normal chow diet to mice fed a Western-type diet–one that was low in complex carbohydrates and fiber and high in fat and simple sugars. Consistent with previous studies from other researchers, they found that the gut microbiota of mice fed the normal chow diet differed from those fed the Western-type diet.

“When the host consumes a diet that’s rich in complex plant polysaccharides (such as fiber), there’s more food available for microbes in the gut, because unlike simple sugars, our human cells cannot use them,” explains Federico Rey, an assistant professor of bacteriology at UW-Madison and the study’s other senior author.

Furthermore, they found that mice given a Western diet didn’t produce certain metabolites at the same levels as mice who ate the healthier diet. “We thought that those metabolites–the short-chain fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are mostly produced by microbial fermentation of fiber–may be important for driving some of the epigenetic effects that we observed in mouse tissues,” Denu says.

The next step was to connect changes in metabolite production to epigenetic changes. When they looked at tissues in the mice, they found differences in global histone acetylation and methylation based on which diet the mice consumed. “Our findings suggest a fairly profound effect on the host at the level of chromatin alteration,” Denu explains. “This mechanism affects host health through differential gene expression.”

To confirm that the metabolites were driving the epigenetic changes, the investigators then exposed germ-free mice to the three short-chain fatty acids via their drinking water to determine if these substances alone were enough to elicit the epigenetic changes. After looking at the mice’s tissues, they found that the epigenetic signatures in the mice with the supplemented water mimicked the mice that were colonized by the microbes that thrive on the healthy diet.

Additional work needs to be done to translate these findings from mice into humans. “Obviously that’s a complex task,” Denu says. “But we know that human microbial communities also generate these short-chain fatty acids, and that you find them in the plasma in humans, so we speculate the same things are going on.”

Rey adds that butyrate-producing bacteria tend to occur at lower levels in people with diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and butyrate is also thought to have anti-inflammatory effects in the intestine.

But the investigators don’t advocate supplementing the diet with short-chain fatty acids as a way around eating healthy. “Fruits and vegetables are a lot more than complex polysaccharides,” Rey says. “They have many other components, including polyphenols, that are also metabolized in the gut and can potentially affect chromatin in the host in ways that we don’t yet understand. Short-chain fatty acids are the tip of the iceberg, but they’re not the whole story.”

###

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

11/16/2016, Krautkramer et al: “Diet-microbiota interactions mediate global epigenetic programming in multiple host tissues.” http://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/fulltext/S1097-2765(16)30670-0

Molecular Cell (@MolecularCell), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that focuses on analyses at the molecular level, with an emphasis on new mechanistic insights. The scope of the journal encompasses all of “traditional” molecular biology as well as studies of the molecular interactions and mechanisms that underlie basic cellular processes. Visit: http://www.cell.com/molecular-cell. To receive Cell Press media alerts, please contact press@cell.com.

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not respo

You are what you eat, the old saying goes, but why is that so? Researchers have known for some time that diet affects the balance of microbes in our bodies, but how that translates into an effect on the host has not been understood. Now, research in mice is showing that microbes communicate with their hosts by sending out metabolites that act on histones–thus influencing gene transcription not only in the colon but also in tissues in other parts of the body. The findings publish November 23 in Molecular Cell.

“This is the first of what we hope is a long, fruitful set of studies to understand the connection between the microbiome in the gut and its influence on host health,” says John Denu, a professor of biomolecular chemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and one of the study’s senior authors. “We wanted to look at whether the gut microbiota affect epigenetic programming in a variety of different tissues in the host.” These tissues were in the proximal colon, the liver, and fat tissue.

In the study, the researchers first compared germ-free mice with those that have active gut microbes and discovered that gut microbiota alter the host’s epigenome in several tissues. Next, they compared mice that were fed a normal chow diet to mice fed a Western-type diet–one that was low in complex carbohydrates and fiber and high in fat and simple sugars. Consistent with previous studies from other researchers, they found that the gut microbiota of mice fed the normal chow diet differed from those fed the Western-type diet.

“When the host consumes a diet that’s rich in complex plant polysaccharides (such as fiber), there’s more food available for microbes in the gut, because unlike simple sugars, our human cells cannot use them,” explains Federico Rey, an assistant professor of bacteriology at UW-Madison and the study’s other senior author.

Furthermore, they found that mice given a Western diet didn’t produce certain metabolites at the same levels as mice who ate the healthier diet. “We thought that those metabolites–the short-chain fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are mostly produced by microbial fermentation of fiber–may be important for driving some of the epigenetic effects that we observed in mouse tissues,” Denu says.

The next step was to connect changes in metabolite production to epigenetic changes. When they looked at tissues in the mice, they found differences in global histone acetylation and methylation based on which diet the mice consumed. “Our findings suggest a fairly profound effect on the host at the level of chromatin alteration,” Denu explains. “This mechanism affects host health through differential gene expression.”

To confirm that the metabolites were driving the epigenetic changes, the investigators then exposed germ-free mice to the three short-chain fatty acids via their drinking water to determine if these substances alone were enough to elicit the epigenetic changes. After looking at the mice’s tissues, they found that the epigenetic signatures in the mice with the supplemented water mimicked the mice that were colonized by the microbes that thrive on the healthy diet.

Additional work needs to be done to translate these findings from mice into humans. “Obviously that’s a complex task,” Denu says. “But we know that human microbial communities also generate these short-chain fatty acids, and that you find them in the plasma in humans, so we speculate the same things are going on.”

Rey adds that butyrate-producing bacteria tend to occur at lower levels in people with diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and butyrate is also thought to have anti-inflammatory effects in the intestine.

But the investigators don’t advocate supplementing the diet with short-chain fatty acids as a way around eating healthy. “Fruits and vegetables are a lot more than complex polysaccharides,” Rey says. “They have many other components, including polyphenols, that are also metabolized in the gut and can potentially affect chromatin in the host in ways that we don’t yet understand. Short-chain fatty acids are the tip of the iceberg, but they’re not the whole story.”

###

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

11/16/2016, Krautkramer et al: “Diet-microbiota interactions mediate global epigenetic programming in multiple host tissues.” http://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/fulltext/S1097-2765(16)30670-0

Molecular Cell (@MolecularCell), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that focuses on analyses at the molecular level, with an emphasis on new mechanistic insights. The scope of the journal encompasses all of “traditional” molecular biology as well as studies of the molecular interactions and mechanisms that underlie basic cellular processes. Visit: http://www.cell.com/molecular-cell. To receive Cell Press media alerts, please contact press@cell.com.

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not respo

12 Health Benefits of Beetroot Juice

Posted: November 20, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a comment

The beet is a bulbous, sweet root vegetable that most people either love or hate. It’s not new on the block, but it’s risen to superfood status over the last decade or so. Research shows drinking beetroot juice may benefit your health. Here’s how.

1. Helps lower blood pressure- Beetroot juice may help lower your blood pressure. Researchers found that people who drank 8 ounces of beetroot juice daily lowered both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Nitrates, compounds in beetroot juice that convert into nitric acid in the blood and help widen and relax blood vessels, are thought to be the cause.

2. Improves exercise stamina- According to a small 2012 study, drinking beetroot juice increases plasma nitrate levels and boosts physical performance. During the study, trained cyclists who drank 2 cups of beetroot juice daily improved their 10-kilometer time trial by approximately 12 seconds, while also reducing their maximum oxygen output.

3. May improve muscle power in people with heart failure- Results of a 2015 study suggest further benefits of nitrates in beetroot juice. The study showed that people with heart failure experienced a 13 percent increase in muscle power two hours after drinking beetroot juice.

4. May slow the progression of dementia- According to a 2011 study, nitrates may help increase blood flow to the brain in older people and help slow cognitive decline. After participants consumed a high-nitrate diet which included beetroot juice, their brain MRIs showed increased blood flow in the frontal lobes. The frontal lobes are associated with cognitive thinking and behavior. More studies are needed. But the potential of a high-nitrate diet to help prevent or slow dementia is promising.

5. Helps you maintain a healthy weight- Straight beetroot juice is low in calories and has virtually no fat. It’s a great option for your morning smoothie to give you a nutrient and energy boost as your start your day.

6. May prevent cancer- Beets get their rich color from betalaines. Betalaines are water-soluble antioxidants. According to a 2014 study, betalaines have chemo-preventive abilities against some cancer cell lines. Betalaines are thought to be free radical scavengers that help find and destroy unstable cells in the body.

7. Good source of potassium- Potassium is a mineral electrolyte that helps nerves and muscles function properly. If potassium levels get too low, fatigue, weakness, and muscle cramps can occur. Very low potassium may lead to life-threatening abnormal heart rhythms. Beets are rich in potassium. Drinking beetroot juice in moderation can help keep your potassium levels optimal.

8. Good source of other minerals- Your body can’t function properly without essential minerals. Some minerals boost your immune system while others support healthy bones and teeth. Besides potassium, beetroot juice provides:

- calcium

- iron

- magnesium

- manganese

- phosphorous

- sodium

- zinc

- copper

- selenium

9. Provides vitamin C- Beetroot juice is a good source of vitamin C. Vitamin C is an antioxidant that helps boost your immune system and protect cells from damaging free radicals. It also supports collagen production, wound healing, and iron absorption.

10. Supports your liver- If your liver becomes overloaded due to the following, it may lead to a condition known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:

- a poor diet

- excessive alcohol consumption

- exposure to toxic substances

- sedentary lifestyle

Beetroot contains betaine, a substance that helps prevent or reduce fatty deposits in the liver. Betaine may also help protect your liver from toxins.

11. Good source of folate- Folate is a B vitamin that helps prevent neural tube defects such as spinal bifida and anencephaly. It may also decrease your risk of having a premature baby. Beetroot juice is a good source of folate. If you’re of childbearing age, adding folate to your diet can help you get the 600 mcg recommended amount.

12. May reduce cholesterol- If you have high cholesterol, consider adding beetroot juice to your diet. A 2011 study on rats found that beetroot extract lowered total cholesterol and triglycerides and increased HDL (good) cholesterol. It also reduced oxidative stress on the liver. Researchers believe beetroot’s cholesterol-lowering potential is likely due to its phytonutrients like flavonoids.

Precautions- Your urine and stools may turn red or pinkish after eating beets. This condition, known as beeturia, is harmless. But it may be startling if you don’t expect it. If you have low blood pressure, drinking beetroot juice regularly may increase the risk of your pressure dropping too low. Monitor your blood pressure carefully. If you’re prone to calcium oxalate kidney stones, don’t drink beetroot juice. Beets are high in oxalates, which are naturally occurring substances that form crystals in your urine. They may lead to stones.

Next steps- Beets are healthy no matter how you prepare them. But juicing beets is a superior way to enjoy them because cooking beets reduces their nutritional profile. If you don’t like beetroot juice straight up, try adding some apple slices, mint, citrus, or a carrot to cut through the earthy taste.

If you decide to add beetroot juice to your diet, take it easy at first. Start by juicing half a small beetroot and see how your body responds. As your body adjusts, you can drink more.

Cooking with Vegetable Oils Releases Toxic Cancer-Causing Chemicals

Posted: November 17, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health, Non-Toxic Choices Leave a commentScientists warn against the dangers of frying food in sunflower oil and corn oil over claims they release toxic chemicals linked to cancer.

Cooking with vegetable oils releases toxic chemicals linked to cancer and other diseases, according to leading scientists, who are now recommending food be fried in olive oil, coconut oil, butter or even lard.

The results of a series of experiments threaten to turn on its head official advice that oils rich in polyunsaturated fats – such as corn oil and sunflower oil – are better for the health than the saturated fats in animal products.

Scientists found that heating up vegetable oils led to the release of high concentrations of chemicals called aldehydes, which have been linked to illnesses including cancer, heart disease and dementia.

Martin Grootveld, a professor of bioanalytical chemistry and chemical pathology, said that his research showed “a typical meal of fish and chips”, fried in vegetable oil, contained as much as 100 to 200 times more toxic aldehydes than the safe daily limit set by the World Health Organisation.

In contrast, heating up butter, olive oil and lard in tests produced much lower levels of aldehydes. Coconut oil produced the lowest levels of the harmful chemicals.

Concerns over toxic chemicals in heated oils are backed up by separate research from a University of Oxford professor, who claims that the fatty acids in vegetable oils are contributing to other health problems.

Professor John Stein, Oxford’s emeritus professor of neuroscience, said that partly as a result of corn and sunflower oils, “the human brain is changing in a way that is as serious as climate change threatens to be”.

Because vegetable oils are rich in omega 6 acids, they are contributing to a reduction in critical omega 3 fatty acids in the brain by replacing them, he believes.

“If you eat too much corn oil or sunflower oil, the brain is absorbing too much omega 6, and that effectively forces out omega 3,” said Prof Stein. “I believe the lack of omega 3 is a powerful contributory factor to such problems as increasing mental health issues and other problems such as dyslexia.”

“People have been telling us how healthy polyunsaturates are in corn oil and sunflower oil. But when you start messing around with them, subjecting them to high amounts of energy in the frying pan or the oven, they undergo a complex series of chemical reactions which results in the accumulation of large amounts of toxic compounds.”

The findings are contained in research papers. Prof Grootveld’s team measured levels of “aldehydic lipid oxidation products” (LOPs), produced when oils were heated to varying temperatures. The tests suggested coconut oil produces the lowest levels of aldehydes, and three times more aldehydes were produced when heating corn oil and sunflower oil than butter.

The team concluded in one paper last year: “The most obvious solution to the generation of LOPs in culinary oils during frying is to avoid consuming foods fried in PUFA [polyunsaturated fatty acid]-rich oils as much as possible.”

Prof Grootveld said: “This major problem has received scant or limited attention from the food industry and health researchers.” Evidence of high levels of toxicity from heating oils has been available for many years, he said.

Health concerns linked to the toxic by-products include heart disease; cancer; “malformations” during pregnancy; inflammation; risk of ulcers and a rise in blood pressure.

10 Smoothie Add-Ins That Fight Chronic Inflammation

Posted: November 16, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentFrom Prevention Magazine

“When inflammation becomes chronic, it’s like having the alarm bells going off in your body 24/7,” warns Michelle Babb, MS, RD, author of Anti-Inflammatory Eating for a Happy Healthy Brain. “Those signals become maladaptive and can lead to chronic disease.”

Enter smoothies—the easiest way to sneak more anti-inflammatory foodsinto your diet, if you load them with the right superfood ingredients. Here are 10 tasty additions that will elevate your blended drink to disease-fighting status. (Want to pick up some healthier habits? Sign up to get healthy living tips, slimming recipes and more delivered straight to your inbox!)

Turmeric

Turmeric is like anti-inflammatory gold. The Indian spice adds color and a sweet-bitter kick to smoothies, plus a hefty dose of anti-inflammatory flavonoids, notably curcumin, that work by lowering histamine and enzymes linked to inflammation. Studies have found that curcumin can improve brain function and even reduce arthritis pain as much as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Pairs with: Banana, mango, carrots, orange, pineapple, coconut milk or coconut water

Acai powder

Made from freeze-dried acai berries, acai powder is packed with anthocyanins, health-promoting antioxidants that reduce inflammation and may help prevent disease. The sweet-tart dust works by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteins that can cause inflammation and pain. The Amazonian berry also delivers inflammation-fighting fatty acids for a mood and brain boost.

Pairs with: Kale, spinach, chocolate/cocoa, banana, almond butter

Berries

Blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, and cranberries have a super power in common: They’re packed with antioxidants to squelch inflammation-causing free radicals. “I recommend mixed berries because they each contain unique phytonutrients,” says Babb. “Blueberries get a lot of accolades, but raspberries are also high in antioxidants and contain a potent dose of ellagic acid, which is anti-inflammatory.”

Pairs with: Banana, bananas, avocado, mango

Tart cherry juice

Tart cherry juice may relieve your aches and pains. Hailed as having the “highest anti-inflammatory content of any food” by researchers at OregonHealth & Science University, studies have shown that drinking the sour stuff can reduce muscle pain and weakness after exercise. So what’s the secret ingredient? As well as antioxidants and anthocyanins, there are 30-plus compounds in this beverage that could squash inflammation.

Pairs with: Lime, mango, orange, coconut milk

Cocoa powder

Permission to eat chocolate, granted! Studies show that flavanol-rich cocoa can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory molecules involved in inflammation, cutting heart disease and stroke risk. What’s more, scientists from Louisiana State University found that cocoa powder is converted into molecules in our guts that reduce inflammation. Opt for regular or raw cocoa powder (skip the “Dutch process”) for the most flavanols.

Pairs with: Banana, nut butter, blueberry, cherry, acai, yogurt, matcha, coconut

“Baby kale is packed with vitamin K, which helps shut down the inflammatory process, and it’s milder than grown-up kale, so it’s easy to disguise in a smoothie,” says Babb. The little lettuce is also rich in the mineral magnesium, known to help reduce chronic inflammation.

Pairs with: Pineapple, mango, orange, lemon, kiwi

Ginger

Ginger doesn’t just soothe an upset stomach; the slightly spicy root acts as an anti-inflammatory, too. Researchers from the University of Miami found ginger significantly reduced knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis and may even work as a natural ibuprofen.

Pairs with: Leafy greens, lemon, coconut, pineapple, apple, chocolate

Matcha powder

Move over, green tea! Matcha, the powdered form of green tea leaves, is not only an ideal smoothie ingredient; it has 130 times more of the cancer-fighting antioxidant epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). Studies show EGCG has an anti-inflammatory effect on immune cells and could even help treat or prevent autoimmune diseases.

Pairs with: Peaches, mint, cocoa, coconut, vanilla

Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease Is Easier Than You Think

Posted: October 14, 2016 Filed under: Food and it's Impact on Our Health Leave a commentPsychology Today– Science shines new light on root cause of memory problems.

Posted Sep 07, 2016

Do you have Insulin Resistance?

If you don’t know, you’re not alone. This is perhaps the single most important question any of us can ask about our physical and mental health—yet most patients, and even many doctors, don’t know how to answer it.

Here in the U.S., insulin resistance has reached epidemic proportions: more than half of us are now insulin resistant. Insulin resistance is a hormonal condition that sets the stage throughout the body for inflammation and overgrowth, disrupts normal cholesterol and fat metabolism, and gradually destroys our ability to process carbohydrates.

Insulin resistance puts us at high risk for many undesirable diseases, including obesity, heart disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes.

Scarier still, researchers now understand that insulin resistance is a powerful force in the development of Alzheimer’s Disease.

What is insulin resistance?

Insulin is a powerful metabolic hormone that orchestrates how cells access and process vital nutrients, including sugar (glucose).

In the body, one of insulin’s responsibilities is to unlock muscle and fat cells so they can absorb glucose from the bloodstream. When you eat something sweet or starchy that causes your blood sugar to spike, the pancreas releases insulin to usher the excess glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells. If blood sugar and insulin spike too high too often, cells will try to protect themselves from overexposure to insulin’s powerful effects by toning down their response to insulin—they become “insulin resistant.” In an effort to overcome this resistance, the pancreas releases even more insulin into the blood to try to keep glucose moving into cells. The more insulin levels rise, the more insulin resistant cells become. Over time, this vicious cycle can lead to persistently elevated blood glucose levels, or type 2 diabetes.

Insulin resistance and the brain

In the brain, it’s a different story. The brain is an energy hog that demands a constant supply of glucose. Glucose can freely leave the bloodstream, waltz across the blood-brain barrier, and even enter most brain cells—no insulin required. In fact, the level of glucose in the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding your brain is always about 60% as high as the level of glucose in your bloodstream—even if you have insulin resistance—so, the higher your blood sugar, the higher your brain sugar.

Not so with insulin—the higher your blood insulin levels, the more difficult it can become for insulin to penetrate the brain. This is because the receptors responsible for escorting insulin across the blood-brain barrier can become resistant to insulin, restricting the amount of insulin allowed into the brain. While most brain cells don’t require insulin in order to absorb glucose, they do require insulin in order to process glucose. Cells must have access to adequate insulin or they can’t transform glucose into the vital cellular components and energy they need to thrive.

Despite swimming in a sea of glucose, brain cells in people with insulin resistance literally begin starving to death.

Insulin resistance and memory

Source: Suzi Smith, used with permission

Which brain cells go first? The hippocampus is the brain’s memory center. Hippocampal cells require so much energy to do their important work that they often need extra boosts of glucose. While insulin is not required to let a normal amount of glucose into the hippocampus, these special glucose surges do require insulin, making thehippocampus particularly sensitive to insulin deficits. This explains why declining memory is one of the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s, despite the fact that Alzheimer’s Disease eventually destroys the whole brain.

Without adequate insulin, the vulnerable hippocampus struggles to record new memories, and over time begins to shrivel up and die. By the time a person notices symptoms of “Mild Cognitive Impairment” (pre-Alzheimer’s), the hippocampus has already shrunk by more than 10%.

The major hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease—neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid plaques, and brain cell atrophy—can all be explained by insulin resistance. A staggering 80% of people with Alzheimer’s Disease have insulin resistance or full-blown type 2 diabetes. The connection between insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s Disease is now so firmly established that scientists have started referring to Alzheimer’s Disease as “Type 3 Diabetes.”

This does not mean that diabetes causes Alzheimer’s Disease—dementia can strike even if you don’t have diabetes. It’s more accurate to think of it this way: Insulin resistance of the body is type 2 diabetes; insulin resistance of the brain is type 3 diabetes. They are two separate diseases caused by the same underlying problem: insulin resistance.

Are you already on the road to Alzheimer’s Disease?

You may be surprised to learn that Alzheimer’s Disease begins long before any symptoms appear.

The brain sugar processing problem caused by insulin resistance is called “glucose hypometabolism.” This simply means that brain cells don’t have enough insulin to burn glucose at full capacity. The more insulin resistant you become, the more sluggish your brain glucose metabolism becomes. Glucose hypometabolism is an early marker of Alzheimer’s disease risk that can be visualized with special brain imaging studies called PET scans. Using this technology to study people of different ages, researchers have discovered that Alzheimer’s Disease is preceded by DECADES of gradually worsening glucose hypometabolism.

Brain glucose metabolism can be reduced by as much as 25% long before any memory problems become obvious. As a psychiatrist who specializes in the treatment of college students, I find it positively chilling that scientists have found evidence of glucose hypometabolism in the brains of women as young as 24 years old.

Real hope for your future

We used to feel helpless in the face of Alzheimer’s Disease because we were told that all of the major risk factors for this devastating condition were beyond our control: age,genetics, and family history. We were sitting ducks, living in fear of the worst—until now.

The bad news is that insulin resistance has become so common that chances are you already have it to some degree.

The good news is that insulin resistance is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease that you CAN do something about.

Eating too many of the wrong carbohydrates too often is what causes blood sugar and insulin levels to rise, placing us at high risk for insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s Disease. Our bodies have evolved to handle whole food sources of carbohydrates like apples and sweet potatoes, but they simply aren’t equipped to cope with modern refined carbohydrates like flour and sugar. Simply put, refined carbohydrates cause brain damage.

You can’t do anything about your genes or how old you are—but you can certainly change how you eat. It’s not about eating less fat, less meat, more fiber, or more fruits and vegetables. Changing the amount and type of carbohydrate you eat is where the money’s at.

Three steps you can take right now to minimize your risk for Alzheimer’s Disease

1. Find out how insulin resistant you are. Your health care provider can estimate where you are on the insulin resistance spectrum using simple blood tests such as glucose, insulin, triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels, in combination with other information such as waist measurement and blood pressure. In my article How to Diagnose, Prevent and Treat Insulin Resistance, I include a downloadable PDF of tests with healthy target ranges for you to discuss with your health care provider, and a simple formula you can use to calculate your own insulin resistance.

2. Avoid refined carbohydrates like the plague, starting right now. Even if you don’t have insulin resistance yet, you remain at high risk for developing it until you kick refined carbohydrates such as bagels, juice boxes and granola bars to the curb. For clear definitions and a list of refined foods to avoid:http://www.diagnosisdiet.com/refined-carbohydrate-list/

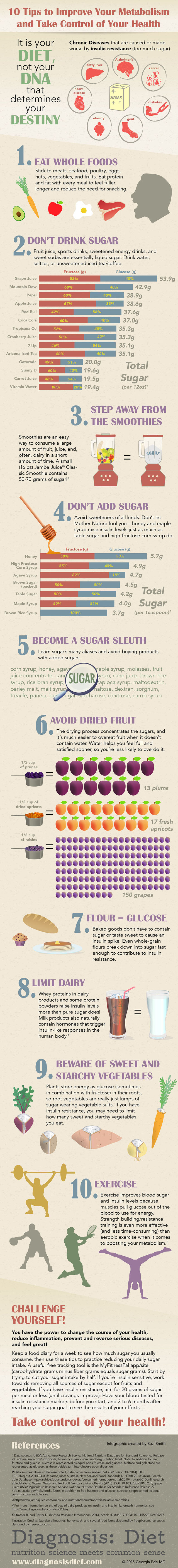

3. If you have insulin resistance, watch your carbohydrate intake. Unfortunately, people with insulin resistance need to be careful with all carbs, not just the refined ones. Replace most of the carbs on your plate with delicious healthy fats and proteins to protect your insulin signaling system. The infographic below provides key strategies you’ll need to normalize blood sugar and insulin levels.

You can wield tremendous power over insulin resistance—and your intellectual future—simply by changing the way you eat. Laboratory tests for insulin resistance respond surprisingly quickly to dietary changes—many people see dramatic improvements in their blood sugar, insulin, and triglyceride levels within just a few weeks.

If you already have some memory problems and think it’s too late to do anything about it, think again! This 2012 study showed that a low-carbohydrate high-fat diet improved memory in people with “Mild Cognitive Impairment” (Pre-Alzheimer’s Disease) in only six weeks.

Yes, it is difficult to remove refined carbohydrates from the diet—they are addictive, inexpensive, convenient, and delicious—but you can do it. It is primarily your diet, not your DNA, that controls your destiny. You don’t have to be a sitting duck waiting around to see if Alzheimer’s Disease happens to you. Armed with this information, you can be a proactive swimming duck sporting a big beautiful hippocampus who gets to keep every single one of your marbles for the rest of your life.